Orban’s father was involved in controversial road construction

For years, one Hungary’s most expensive state infrastructure projects, the construction of the M4 road, connecting Budapest with the Hungarian-Romanian border, has been stalling. The high costs of the investment had previously been criticized by the European Union, but the Hungarian government stood behind the construction – during the time when Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and Lajos Simicska, a Hungarian oligarch whose company participated in the construction, were close allies.

In the spring of 2015, shortly after Orbán and Simicska had turned agains each other, one phase of the construction (carried out by Közgép, a company then belonging to Simicska), was suspended by the government. According to János Lázár, who headed the Prime Minister’s Office at the time, the costs of the suspended construction were “magical,” “one kilometer of road in the flat Great Plain costs 4 billion forints (11 million euros).” Lázár also predicted that the suspension of the construction would make it possible to “inspect each and every invoice” of the construction.

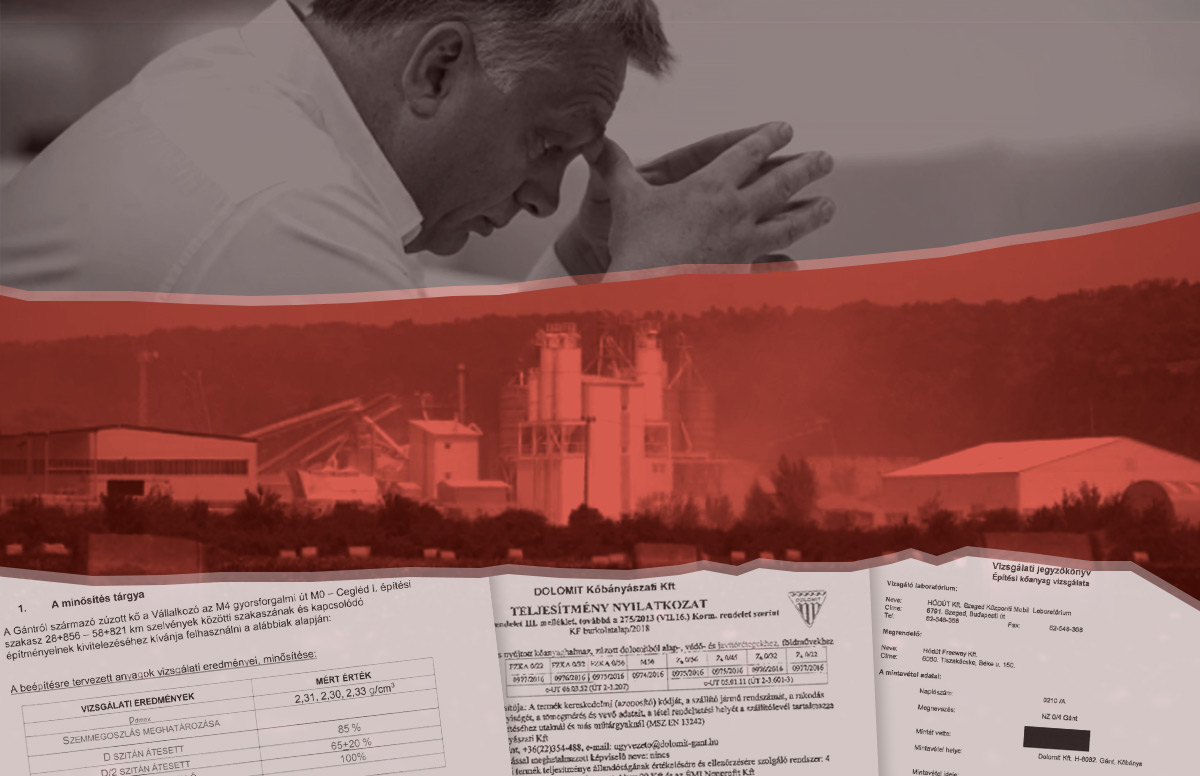

Although the Hungarian government has not published the results of these inspections since then, Direkt36 has obtained the detailed documentation of the project. These revealed that the company of Orbán’s father also took part in the costly state project: his mining company, Dolomit Kft., delivered crushed stone to the construction. Among other things, the asphalt mixture of the M4, the roadside and the stop lane were made of stones of the mine owned by Orbán’s father.

Even though during his first term as a prime minister, Viktor Orbán asked his father not to participate in state projects, in our series of articles we revealed that the father’s companies have been involved in several public works, which contributed to the spectacular growth of his businesses.

We asked Dolomit Kft. and the main contractors involved in the construction of the M4 about the exact amount and value of building materials supplied by the company of Orbán’s father, but they did not answer our questions. Nor did the prime minister respond to our questions about his father’s involvement in state projects.

The companies of the Orbán family usually participate in public projects as suppliers of building materials. As there is no publicly available information about the suppliers of state projects, Direkt36 launched a public information lawsuit in 2017, in order to get detailed information about 6 large infrastructure projects. The Hungarian Civil Liberties Union (HCLU) Dr. Zsolt Szegedi provided legal help. As a result, we received 28 cardboard boxes with more than a hundred thousand pages of documents – this is where we found evidence that proves that the company of Viktor Orbán’s father was involved in the construction of M4.

After the Orbán-Simicska conflict, the government realized that the road was expensive

The M4 was originally designed as a highway to replace one of the busiest and most accident-prone sections of the Hungarian road network, today’s road 4 (Budapest-Szolnok-Püspökladány) and road 42, leading to the Romanian border (Püspökladány-Berettyóújfalu-Ártánd).

The first section of M4 was completed in 2009, under the socialist government, but most of the investment took place during the Orbán government. However, the construction has been slower and more expensive than planned: so far, less than 100 kilometers of road were finished out of the planned more than 200 kilometers.

The construction of a 28-kilometer section of the project (between Abony and Fegyvernek) started in 2013, when the prime minister and his old friend, Lajos Simicska, previously the economic director of Fidesz, were still close allies. Besides big international construction companies, Közgép, a company belonging to Simicska at the time, also received a valuable contract for the construction of the section, built from more than 110 billion forints (over 300 million euros).

The Hungarian government planned to finance the construction of this section from EU funds, but the European Commission raised concerns over various aspects of the project, including its extremely high price. In response, the government withdrew its funding application in 2014, but continued to stand behind the project. Shortly after the Orbán-Simicska war, however, the government’s position suddenly changed: the construction of the Abony-Fegyvernek section was suspended on the grounds of cartel suspicion, and at the same time, the win streak of Közgép also ended on public tenders.

As we revealed earlier, the businesses of the Orbán family started to show spectacular growth, partly thanks to state contracts, after the outbreak of the conflict with Simicska.

Until then, it was Simicska’s taskto limit the family businesses’ involvement in public projects, in order to spare Orbán from similar political attacks he had come under during his first term as prime minister between 1998 and 2002, when he was frequently criticized because of his father’s alleged involvement in state projects.

After the conflict between Simicska and Orbán, this restriction was lifted. As documents prove, the company of Orbán’s father remained involved in the construction of the M4 even after the government began to criticize the project. According to one document, building materials had also been ordered for the Abony-Fegyvernek section from Dolomit Kft.

Gánt’s excellent stones

The building materials supplied by the Orbán company were delivered to the road section between Üllő-Albertirsa and Albertirsa-Cegléd.

In the documentations from 2017 and 2018 of these constructions, we have found dozens of documents bearing the name of Dolomit Kft. Among other things, documents presenting the materials used for the construction; the company’s performance declarations for its own products; and various test reports.

A 2018 document also details that the crushed stone from Dolomit Kft. in Gánt was planned to be used on the section between Üllő-Albertirsa for the construction of a pavement and an unpaved stop lane, as well as for the base layer of the road. During the examination of the stone material, they came to the conclusion that the crushed stone from Dolomit Kft. can be classified as an “excellent, well-compacted and frost-resistant” material.

Previously, several construction sources told Direkt36 that the products supplied by Dolomit Kft. are of good quality, but they are up to thirty percent more expensive than the products of the competition. It is not clear from the project documents exactly how much building material Dolomit Kft. supplied for the construction of the M4, and therefore how much money it received.

An earlier document, dated November 2014, suggests that Orbán’s father’s company had already delivered stone to the Abony-Fegyvernek section, which was shut down later. At that time, at the request of one of the main contractors working on the section, Colas Hungária Zrt., a railway transport company made an offer for the delivery of crushed stone to the M4.

The company offered a transport fee of HUF 1,200 per ton for the Bicske-Szolnok route, and it cost another HUF 1,200 per ton to transport the stones from Gánt to Bicske and load them into wagons. Although the document does not name Dolomit Ltd., it notes that the fee for the Gánt-Bicske section is invoiced by the “Dolomit mine”.

Since no other dolomite mine operates in Gánt, it is likely that crushed stone was planned to be transported from the Orbán family mine for construction more than 170 kilometers away. Such a distance may seem like a lot, but it’s not necessarily blatant, a construction source told Direkt36, who is familiar with the details of several major state road construction projects. “They usually try to bring building materials from as close as possible to construction sites, but there is not always a mine with adequate capacity nearby. For example, there is none in the Great Plain,” he said.

Whether Colas accepted the quote and how much building material was ultimately delivered from Dolomit Kft, is not detailed in the project documents, and the companies involved did not answer our questions either.

The mine brings billions to the Orbán family

In recent years, Direkt36 has found many pieces of evidence that companies in Viktor Orbán’s family receive public money from state projects, in several cases through the companies of Lőrinc Mészáros.

Dolomit Ltd. has been one of the most successful companies in the market for many years, but in 2018 it outperformed all of its major competitors in one important aspect: Győző Orbán’s company achieved the highest profit margin (41,3%), which even rose further last year to 45%. The profit margin shows how much profit the company made in relation to sales. Most recently, in 2019, the mining company of Orbán’s father closed the year with a profit of 1.8 billion forints (5 million euros), which the owners all took out of the company as dividend payments.

For Hungarian company data, we used the services of Opten.

Gergő Sáling and Fanni Matyasovszki helped to process the documents.