“Seller shall not undertake maintenance” – hospitals struggled with smoking, incompatible Chinese ventilators

In May 2020, after a morning meeting of the Epidemiological Operational Group, a tense meeting was held in the Budapest headquarters of the National Directorate General for Disaster Management. At the call of the Hungarian government, about a dozen professionals gathered in a room: mostly CEOs and senior technicians of companies specializing in ventilators. A government official greeted them and said the Ministry of Foreign Affairs had imported thousands of ventilators from China and someone had to install and calibrate them. Several models were displayed in the room and the officials asked the guests to give a price offer for the job, a source who himself attended the meeting told Direkt36.

These Chinese machines had been unknown in Hungary, so the companies took some of their technicians with them for inspection. The experts came to devastating conclusions:

- some of the devices would have required additional disposable or wearing parts, but they were not available in Hungary

- several ventilators lacked CE certification essential for European import of goods

- some of the inspected ventilators had incompatible connectors, and appropriate adapters were missing

- the software running on the machines was unknown to Hungarian experts

A technician of one of the companies, after inspecting the ventilators, said in desperation, “what would they do if a problem occurred, and a patient died”.

Eventually, the ventilator companies refused the government’s request. In the end, only a small company and another company that hadn’t dealt with ventilators before at all took on the task.

This was the beginning of the story of the roughly 16,000 Chinese ventilators in Hungary, of which only about 3,000 ended up in Hungarian healthcare institutions. Direkt36 talked to sources from hospitals, ventilator specialists, examined contracts and other documents to find out what happened to the ventilators put in use to fight coronavirus.

Our research showed that many hospitals were wary of the Chinese ventilators, many of which are kept unused in their storages. The supply is so plentiful that if one goes bad, hospitals will unpack another instead of repairing it. Technical errors occurred in several towns, for example, in a Western Hungarian hospital, several devices started smoking the moment they were connected to the electric grid. In another hospital in the capital, technicians were not even able to put the ventilators into use. And even the manufacturer of the best-regarded Chinese model, the VG70, issued several “urgent field safety notices” about bugs in its own product’s software or controversies in the manual.

Hungarian government purchased the Chinese ventilators in the panicky atmosphere of the first wave of Covid-19. Coronavirus arrived in Europe with devastating effects, countries competed to buy medical supplies.

In this situation, the Hungarian Ministry of Foreign Affairs contracted to purchase many thousands of such devices without considering who would put the machines into operation, and claimed almost no guarantee from the manufacturers, which would have protected the interests of the Hungarian state in case of non-conformity.

OKFŐ, the government body managing Hungarian health care institutions has not answered our questions, neither did the Chinese manufacturers and hospitals involved in the story. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs, although it failed to answer the specific questions, sent a reaction, according to which, there was “brutal competition for ventilators at the time, it was not possible to regard standard market prices and conditions, but in this competition, Hungary stood its ground.”

“Buyer acknowledges that repairs may take up to two months”

In March 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, led by Péter Szijjártó, began to search for ventilators for sale and eventually spent about 300 billion forints to buy 16,000 ventilators. Worst-case scenarios at the time counted with a maximum of 8,500 patients simultaneously in need of invasive ventilation.

The ministry bought ventilators in large batches through companies with Chinese, Malay, Slovak or Hungarian companies, but it is clear from the contracts that the devices procured this way were not only extremely expensive, but also sloppy and severely disadvantageous for the Hungarian party.

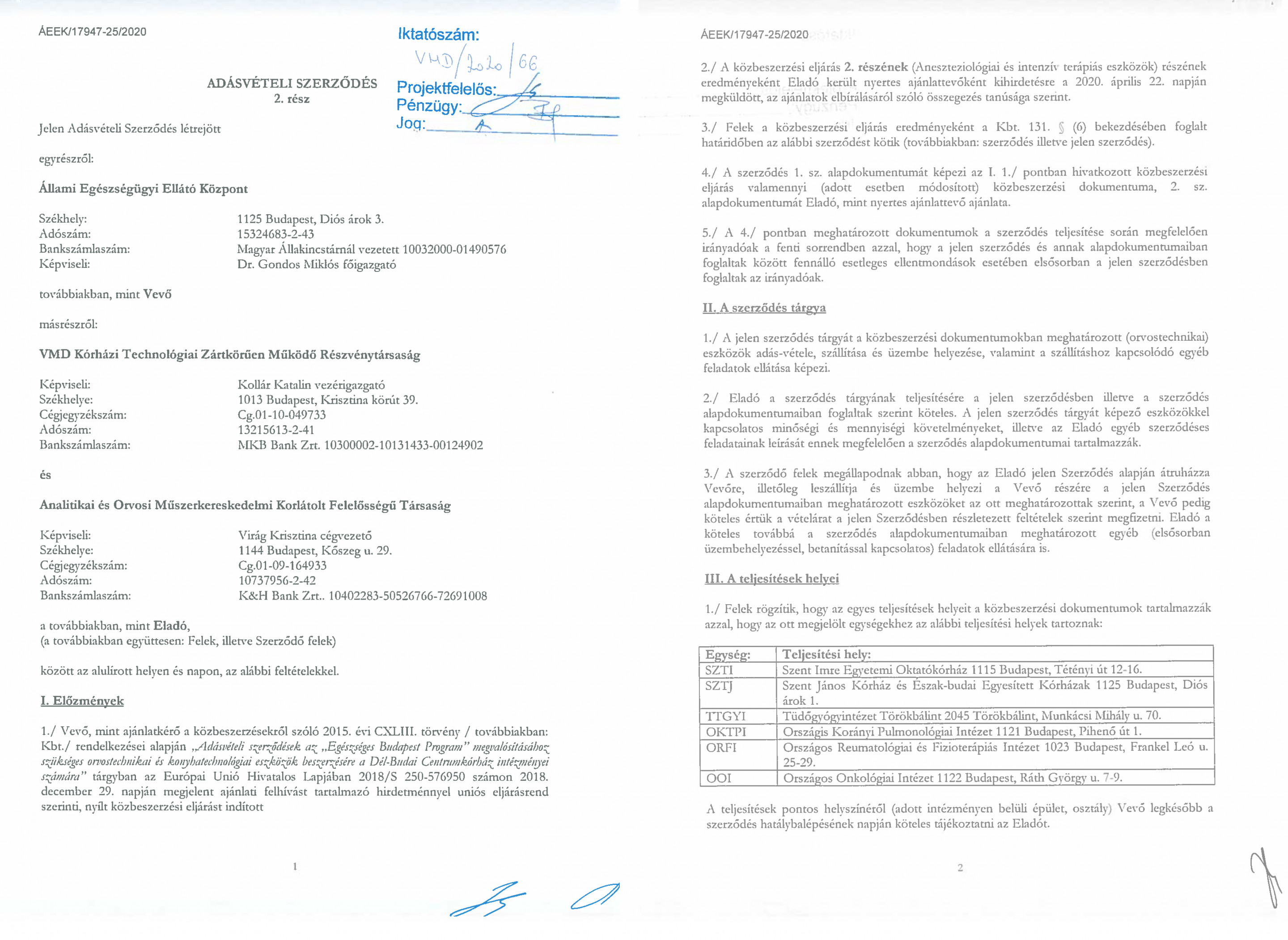

For example, a thorough contract that includes quality guarantees looks like this:

This is a 13-page contract concluded following a public procurement procedure, in which the buyer (the government body responsible for health care supplies) receives detailed guarantees for the quality and standard of the ventilators. Among other things, it regulates the delivery and acceptance, stipulates that the delivery companies undertake the installation, the necessary repairs, and the replacement of parts.

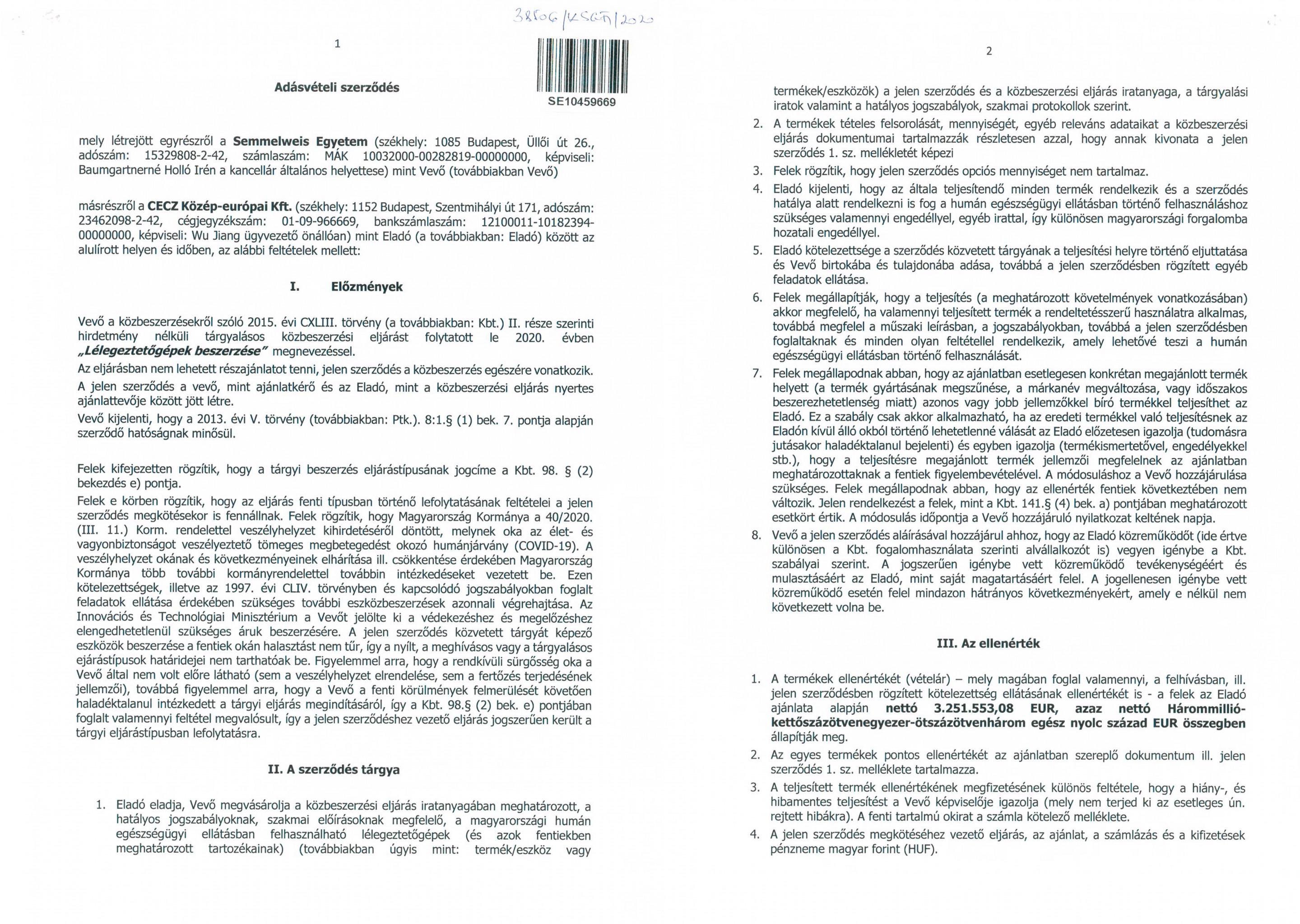

Semmelweis University (SE) also bought ventilators at the beginning of the epidemic, and despite the haste they managed to conduct a simplified public procurement procedure:

This contract also details that the ventilators must be fully licensed and be in a suitable condition for their intended use, otherwise a penalty or compensation will have to be paid.

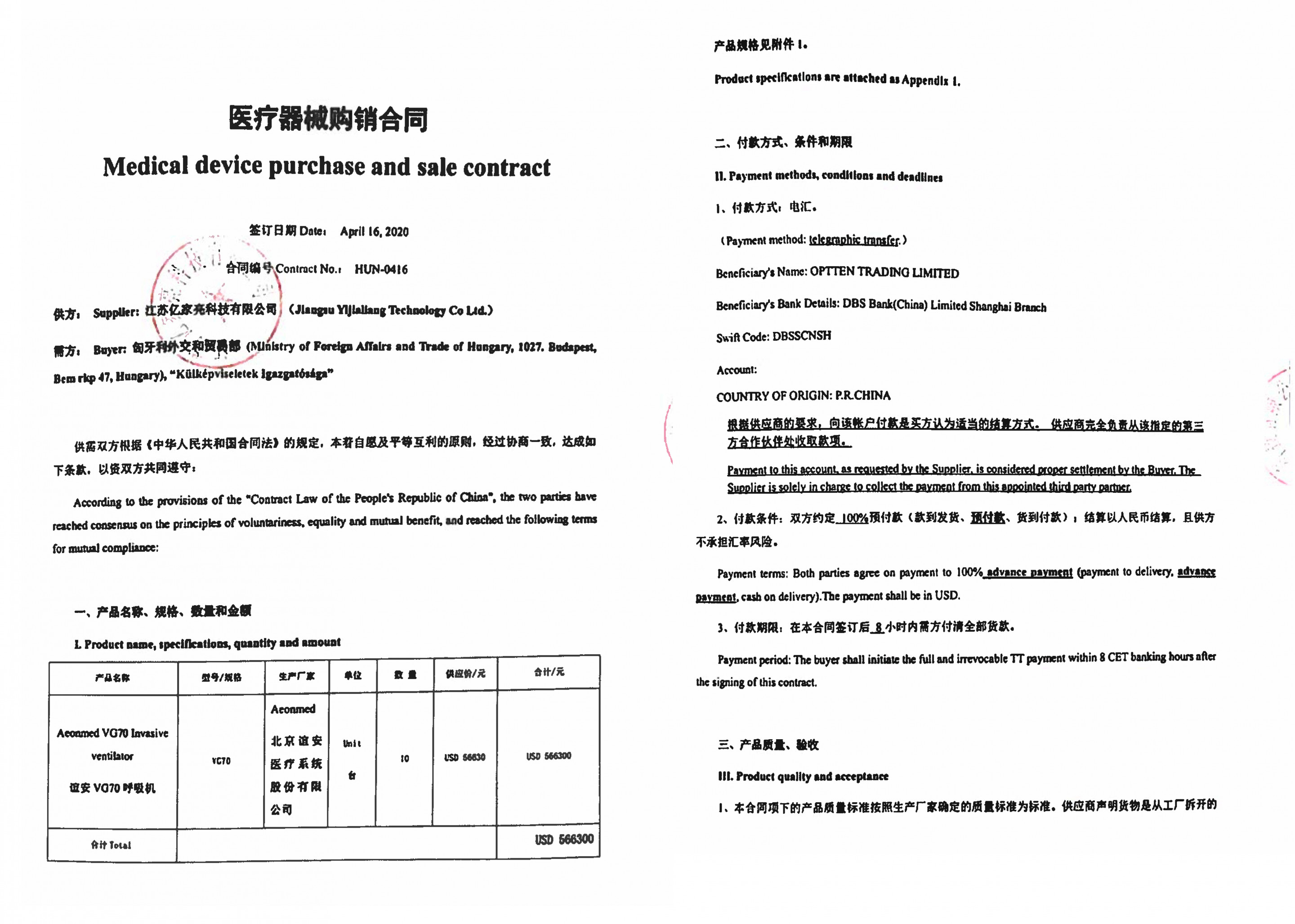

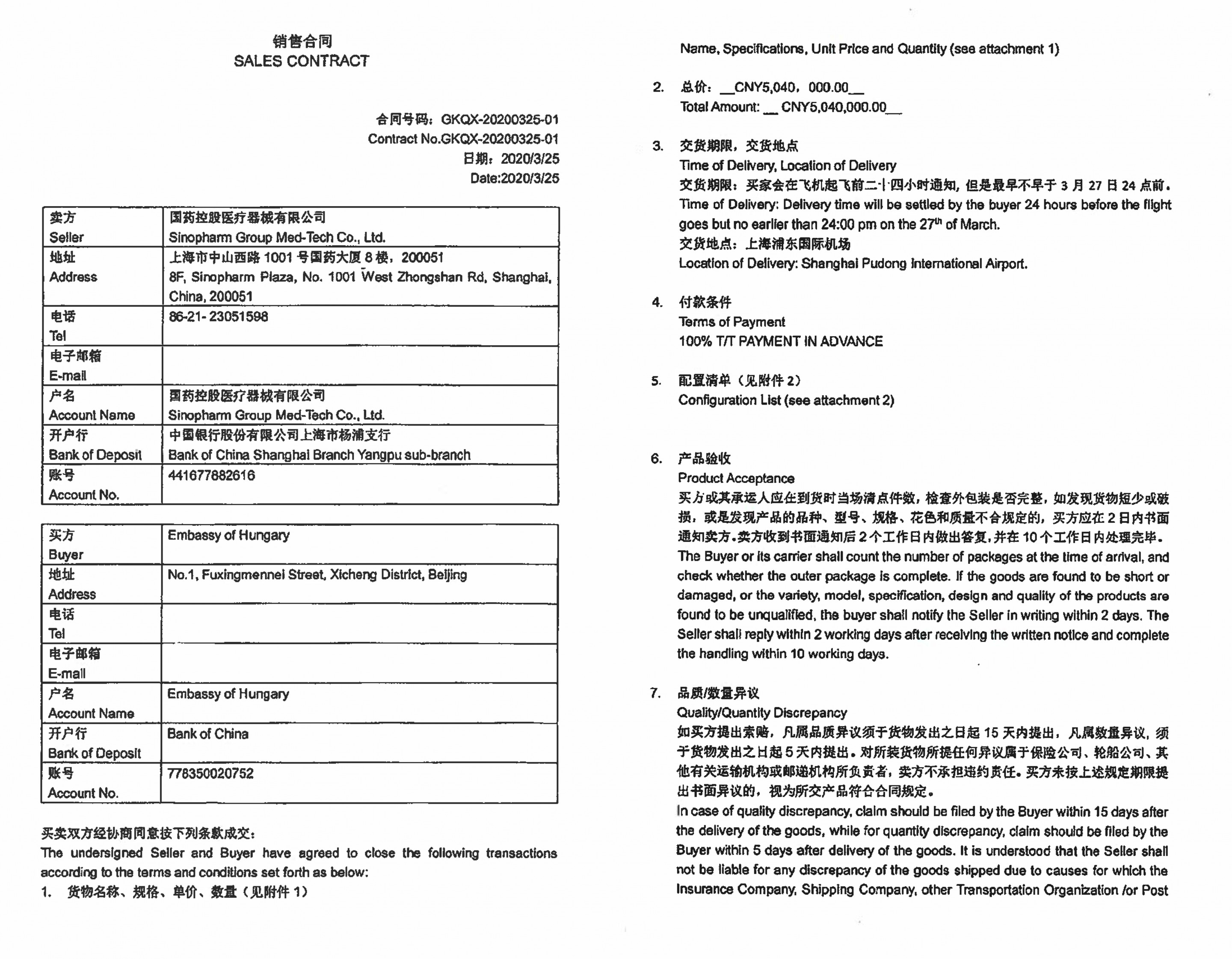

And here is one of the contracts signed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs’ officials (these contracts were made public upon a FOIA request from 444.hu):

Dozens of contracts were signed by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and in almost all cases, 100 percent of the price was paid in advance. In many cases, the sellers were only willing to deliver the packaged goods to Hong Kong, Beijing or Shanghai airports and only accepted a complaint for 2-7 days from receipt, essentially excluding the possibility that the products’ defects be detected during use. A contract, concluded with a company called Europa Asia Trading and Investment Ltd. for USD 51 million (HUF 16.5 billion), even states that

“the buyer expressly waives the right to a penalty for late payment and defective performance in advance,” and notes that “buyer acknowledges that the manufacturer does not have a European maintenance headquarters, so repairs and replacements may take longer than usual, up to two months.”

Most of the contracts are 4-5 pages long and not very detailed: for example, a contract from a Hong Kong company called Manjusaka Jewelers does not even specify exactly what type of equipment it is, it just writes about a thousand “Shangrila brand ventilators that do not require a separate compressor.” The advance paid to the company (USD 11.25 million, approximately HUF 3.6 billion) is non-refundable.

Although some contracts provide for a 12-month warranty, no further details have been set out, while others do not even provide such details, but only state rules of delivery. According to a bilingual contract with Jiangxi Luxin Technologies, written in Chinese and somewhat incorrect English, the parties agree that the company will not undertake maintenance tasks, and if the Hungarians need that, they should contact the manufacturer. According to another, the installation of the devices will have to be done according to video instructions of the manufacturer.

There is a contract in which the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has even said yes to buy ventilators without CE certification, although all goods entering Europe need to comply with European standards and have CE certification.

It is easy to ventilate air, but the doctor’s trust is the essential point

In the case of life-saving medical devices, the provision of maintenance services, which has largely been left out of the contracts, is key because installation, maintenance and repair cannot be carried out without an expert technician who is familiar with the devices. “Technicians, among other things, need to understand lung medicine,” explained the head of a Hungarian company dealing with the distribution of ventilators. During the first start-up, the fine-tuning of the machines is carried out jointly by the medical device technician and the doctor, as the goal is for the machine to work under the doctor’s hands and supplement the therapy.

An advanced ventilator can even self-adapt to changes in a patient’s condition, alerting hospital staff when needed, but only in really justified cases not to unnecessarily disrupt the work of the staff. That is why doctors often prefer trusting older types, because they are already familiar with how they work. “It is easy for a ventilator to ventilate air,” said an instrument technician who has been in the business for decades. Modern machines combine fine operation with ease of use, which simpler machines cannot. According to the source, Chinese market offers high-tech and crappy products at the same time, one has to be very careful when buying medical devices.

But “what happened here was that, with a little exaggeration, everything that someone said was a ventilator was eventually imported to Hungary.”

According to ventilator experts and hospital sources speaking with Direkt36, many of the devices purchased by the Hungarian state came with a Chinese or English interface, although it would be important for hospital workers that the machines can operate in Hungarian. According to the medical device technician with decades of experience in the field, it matters a lot what configuration, additional parts and connectors the machines are equipped with, because a device of the same type can be designed in many ways. During his work, he visited the country’s hospitals: he also encountered four to five designs of the same type of a Chinese ventilator, making it difficult to put it into operation.

This is the reason why the only Hungarian professional ventilator company that participated in the purchases of KKM did not take part in the initial setup of any machines apart from the ones that it imported itself. We are talking about Medirex Zrt., Which imported Beijing Aeonmed VG70 devices from one of the largest Chinese anesthetic and ventilator manufacturers. This is the model that, according to sources reporting to Direkt36, accounted for the largest proportion of Chinese machines that have been delivered to hospitals. A source that knows ventilators described it as falling into the “not good, but usable” category, which was the best choice available at the start of the pandemic.

However, the VG70 had not been known even to Medirex engineers before, so they first gathered intel about the machine through their Chinese contacts and only then undertook to deliver a total of 700 units. They also insisted that the devices are to be sent with accessories that were known to be compatible with Hungarian hospital devices, so they could be put into operation immediately. Thus, Medirex could already install these ventilators in hospitals last summer.

The initial setup of the other machines procured by the government was eventually commissioned through a smaller market player, Endo-Plus-Service Ltd., and a former shipping company, Pannon Cargo & Sped Trans Ltd. Last year both made their year-end financial closures with multi-billion-forint profits: Pannon Cargo, for example, which had previously focused on road haulage and computer programming, increased its profits 4,600 times over the previous year and took out about two billion in dividends this year. Endo-Plus-Service Ltd. did not earn that much, but its profit almost doubled, and its revenue doubled to HUF 3.8 billion. The leaders of the two companies did not wish to answer Direkt36’s questions.

Out of order? There is another one

Problems with the Chinese ventilators began when they were shipped out to hospitals across the country at the end of 2020. At the time, just as it is now, the epidemic was at its peak, and hospitals had to set up new intensive care beds in high stride, and those had to be equipped with ventilators.

At the South-Pest Central Hospital (DPC), problems arose as soon as the Chinese devices arrived. The hospital received 11 ventilators in the first round, but they only found out about it on the day before, so they couldn’t even prepare for the handover, “the technician colleagues were shocked and frustrated,” a hospital source with insight told Direkt36. However, the main concern was that the connectors on the Chinese machines were not compatible with the standard hospital electrical, vacuum, and oxygen connectors, another operative hospital source explained. They did not receive a converter (at the beginning of the epidemic, they were in short supply worldwide, and could only be obtained from China). For this reason, the devices could not be calibrated either, so they had to be taken back to the storage. At the hospital, no official report was written on the problems that emerged during the initial setup process.

In a hospital in Western Hungary, the problem was not with the accessories, but with the ventilators themselves: they started smoking the moment they were connected to the mains. The name of the institution will not be disclosed at the request of our hospital source, because they fear that the staff will get into trouble if details of the case go public. This hospital was hastily trying to expand its intensive care unit beds in early December 2020. They only had a few days to build plasterboard walls, install wires, and place freshly unpacked ventilators next to the beds. Dozens of the VG70 were shipped to the hospital, and about ten percent of them released smoke upon powering up. The faulty machines were pushed aside, and an external technician working on them arranged for their replacement. This incident was similarly not reported according to the hospital source, and since no involvement of the fire department was required, the hospital did not even report the incident.

We tried to inquire about possible technical defects in the VG70 from the Chinese manufacturer Aeonmed, but our questions went unanswered. However, the manufacturer issued several “urgent safety warnings” about its product last year. These can be found around the websites of Western European health authorities. (These, however, are not featured on the website of the Hungarian national authority, the National Institute of Pharmacy and Food Health.) The warnings pertained to software errors: in one case for example, the device issued an error message for a function that was not even implemented into the product. In other cases, the operating manuals contained different instructions compared to what the device was actually offering.

A medical device technician involved with ventilators for decades now, said he has seen tagged-up devices lined up in storages at almost every hospital he has visited in recent months. The tags were bearing notes like “the battery is defective”, “the machine indicates an error”, “the oxygen measurement is not working”.

Several hospital sources have told Direkt36 that devices with technical errors have often not even been repaired, spares were retrieved from the warehouses instead of replacing these faulty machines.

This for example has also happened in Zalaegerszeg, where several Crius Northern V6 devices have failed last year. According to the hospital’s announcement back then, after receiving an error message, the staff replaced patients on other machines. A local hospital source told Direkt36 that there is a multitude of the required amount in the warehouses, so a single failure should not cause a shortage in supply.

No data is available on how many of the devices delivered to hospitals have failed, it is not even public how many were used at all. From the data released to Atlatszo.hu in May 2021, all that is known is that the National Hospital Directorate-General (OKFŐ) shipped a total of 3,288 ventilators to some 80 health facilities in the country, most of which were VG70s (2241 units), but there also were 425 units of Shangrila 510S, manufactured by the Chinese company Aeonmed. Britain also bought the latter type, but British doctors refused to use them because they thought the machines had a fluctuating supply of oxygene, were of poor design, and were intended for use in ambulances rather than intensive care units.

In Hungary, these were shipped out to dozens of hospitals based on data provided by OKFŐ, but it is not known how many of them were used and whether any problems occurred.

Although in theory any unforeseen events related to medical devices should be reported to a state body called the National Institute of Pharmacy and Food Health (OGYÉI), the body has not disclosed any information on how many reports they had received, saying they did not have the required data. We sent our inquiry about this on September 20th, the one-sentence answer arrived three months later. OGYÉI had the right to do so, because with the current state of emergency due to Coronavirus, public authorities may delay responding to FOIA requests for a period of 90 days.

In addition to OGYÉI, the National Hospital Directorate General and the Operational Group also did not answer our inquiries, and neither did South Pest Central Hospital. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs did not answer specific questions, (mainly regarding the contracts they concluded), but sent a general reaction. According to this, Hungary wanted to prepare for the worst-case scenario with the purchase of the ventilators. “There was an enormous competition, it was not possible to regard standard market prices and conditions, but in this competition, Hungary stood its ground. Hungary had access to the required quantity of ventilators, so there wasn’t a case where somebody had no access to one, and this also provided us with the opportunity to sell excess stocks and to be able to aid other countries. ” They added that all ventilators procured by the State Department were “set up and handed over to the National Hospital Directorate-General in perfect operating conditions to save lives”.

Illustration by Szarvas / Telex