In Hungary, land records are public. Except in politically sensitive areas

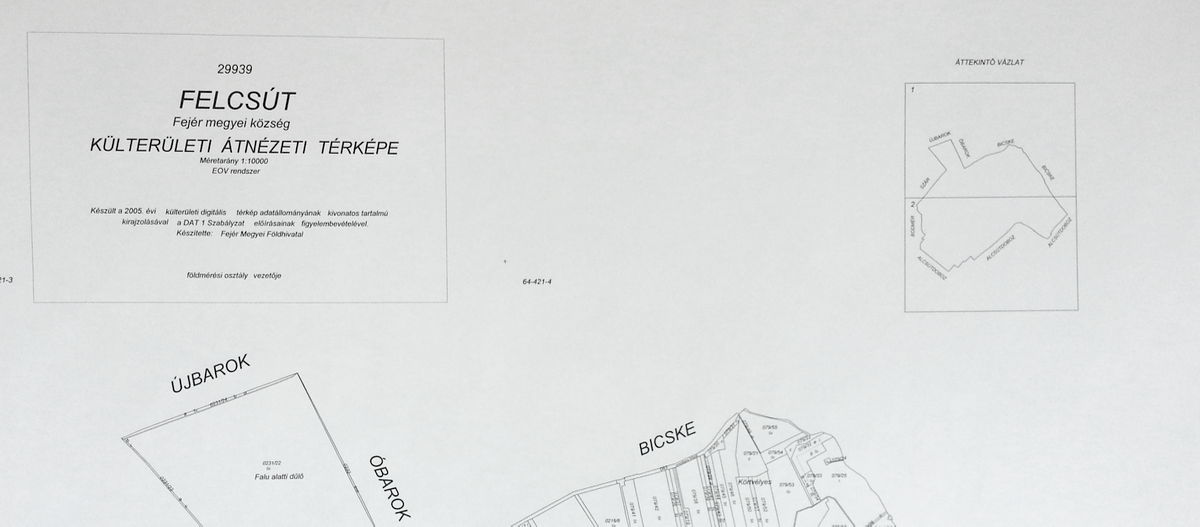

In the past few weeks I have been a frequent visitor at the Bicske office as I wanted to find the owners of several properties around Felcsút. I knew the parcel numbers of the estates, but only the land registry could connect these numbers with information on the owners. At first they were helpful and gave me access to the public data but on Friday the clerk told me she is not allowed to give me any more files.

I asked to speak with the head of the local land registry. She argued that I requested so many documents during the past few weeks that it counts as a so called “bulk data request.” When I asked what the limit of propriety documents is that could be checked at once, she answered that the law on informational self-determination and freedom of information protects all personal data. She then suggested to consult with the head of the district office and asked me to wait on the corridor.

Support Direkt36, invest in democracy!

[vimeo id=”158802467″ align=”center”]

Without limitation

The head of the district office and the head of the land registry spoke for about 40 minutes before they called for me. While I was waiting for them I had the chance to read again the information sheet displayed on the office’s door. “Property records can be viewed and copied without limitation by anyone,” says the sheet hanging on the door of the office I was sent out from because I wanted to look at too many property records from Felcsút.

In order to protect personal data, the land registry has to log who and when viewed which property records. This is the only prerequisite for checking property records. Like everyone who requests property documents, I showed my ID, and filled in a form with my name and other personal data, and the parcel numbers I was interested in. I even disclosed that I wanted to check these parcel numbers as a journalist of Direkt36.

Property records reveal a lot about the real estate in question: its size, type (for example, in cases of lands the property records specify if it is a forest or plough land), its current and former owners, and if there is mortgage on the property. No one can just go to a land registry office and ask if a certain person owns any real estate. For such an inquiry the parcel number or the property’s address is necessary. However, if someone has this latter information the land registry has to provide access to property records on a computer. Copying the records costs some money, but viewing them is free.

In bigger land registries – like the two in Budapest – it is possible to check any amount of property records without the help of the clerks. As far as we know the Bicske land registry had the same system before, but now every property record has to be asked from the clerks, and they don’t even show it to the inquirer, just dictate the data to them.

If someone registers with the Hungarian state’s online administration system, property records can be viewed online for 1000 forints (around 3 euro). There are hundreds of properties around Felcsút, the area we are interested in, so finding what we want online would cost hundreds of thousand of forints (thousand of euros). For this reason, I decided to go after the data and travelled to Bicske, where I had to queue for hours to talk to the lone clerk sitting in the office. If there were people in the queue after me, I only asked 25-30 property records at once and then stood in the queue once again.

The land registry is not right

After consulting for over 40 minutes, the head of the district office, Gábor Szabó, and the head of the land registry told me that my requests count as a “bulk information request” and therefore I have to file a separate data request, specify the purpose of data collection and cite the law that allows such data collection. When I asked which law regulates this process they referred to the freedom of information law and emphasized that the owners concerned in my requests have to agree to provide data about them. This means that, according Szabó, if an owner doesn’t want to be disclosed the land registry won’t tell me his name.

However, Szabó’s opinion contradicts all the provisions on property registration and property records. Therefore I asked them to specify the paragraphs they are citing. Szabó sent me two paragraphs of the law regulating property registration, which said that the land registry has to provide access to property records. They once again referred to the freedom of information act, but the cited paragraph was about different types of data.

I told Szabó that I was going to write an article about what happened and asked him to comment. He said he needed to ask for permission before commenting, so I sent my written question to the Bicske District Office Friday early afternoon. I asked for the reason why they refused to give me access to the data, and whether this decision has anything to do with the prime minister’s and his family’s estate in Felcsút.

We’ll post their answer once it arrives.