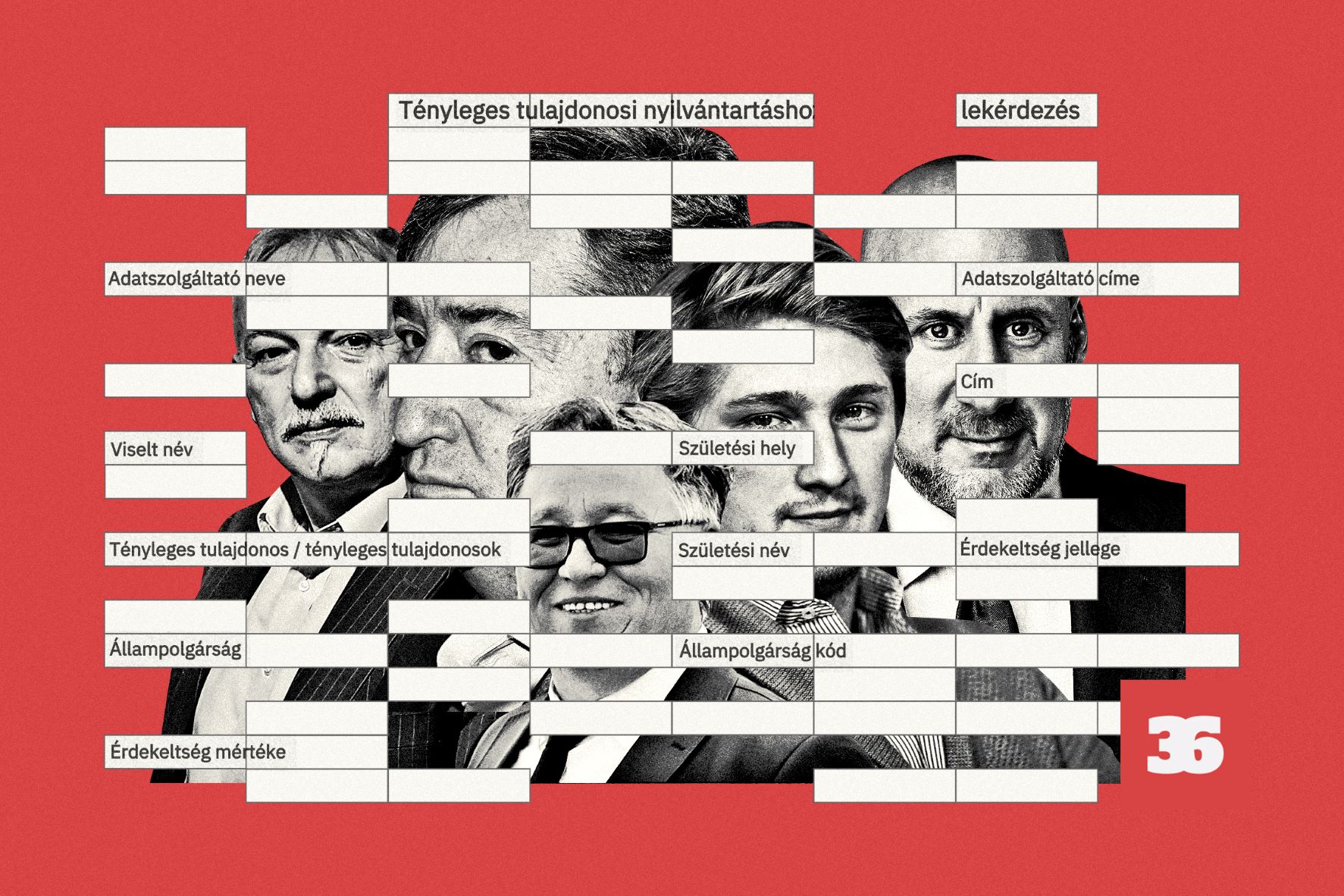

Database exposes Hungarian oligarchs hiding huge fortunes

Documents prove that pro-government businessmen own a number of private equity funds with vast fortunes whose owners have so far remained secret, Direkt36 has learned, using data obtained from a state register.

Among other things, Direkt36 learned the following:

- It turns out that Lőrinc Mészáros, a friend of Prime Minister Viktor Orbán and one of the wealthiest Hungarians, has interest in even more private equity funds than he had been associated with in the press.

- István Száraz, who is a friend of the central bank director’s son, Ádám Matolcsy, is the ultimate beneficial owner of almost 11 per cent of the Hungarian superbank Magyar Bankholding.

- Two private equity funds are owned by a Pécs real estate trader named Áron Hornung, who did business with billionaire investor Dániel Jellinek and has several links to Orbán’s son-in-law’s business partner, Endre Hamar. Hornung’s name has not hit the news before, although last year he took out dividends of HUF 13.5 billion from just one of his companies.

- The private equity fund that won the Hungarian motorway concession for 35 years – in a consortium with six other private equity funds – belongs to billionaire László Szíjj, a business associate of Lőrinc Mészáros.

The special rules applying for private equity funds offer investors the possibility to hide huge fortunes. While in the case of traditional companies anyone can obtain official information about their ownership and finances with a few minutes of online research, private equity funds are different.

It is a form of investment in which a closed circle of investors can put their money and grow their wealth without being subject to company disclosure rules. The money is held by a fund manager company on behalf of the investors. The ownership of the fund manager is public, but it is not possible to find out whose money is in the private equity fund they manage.

Private equity funds exist in many countries around the world, primarily for investment purposes. In Hungary, however, a few years ago, the business elite close to the government saw the potential of their secrecy and started using them like offshore companies are used elsewhere: to increase their wealth in complete secrecy.

As a result, private equity funds have multiplied in Hungary, and hundreds of billions of HUF worth of wealth have been transferred to them. A series of fund managers linked to billionaires close to the government have built ever larger portfolios. Money has been invested in almost every sector of the economy. Private equity funds own, for example, the 35-year-old Hungarian motorway concession, hotel chains, dozens of Budapest’s luxurious palaces, restaurants, banks, industrial companies, waste treatment plants and many others. Valuable state-owned properties and companies have also been transferred to private equity funds, ultimately enriching the wealth of unknown individuals. Last year, business site G7 estimated that the total anonymity scheme was so widespread among large investors that by 2021, 3.5 percent of all Hungarian companies’ profits were realized in private equity funds.

Direkt36 has now found the ultimate beneficial owners of about a fifth of the operating private equity funds, 26 in total, in a state database managed by the tax authority NAV. This is a register of beneficial ownership, created in response to an EU requirement and currently available to anyone for a small fee.

It is not clear whether the ultimate beneficial owners of private equity funds should be included in the register maintained by the NAV. There are conflicting laws and different definitions of who should be considered the ultimate beneficial owner.

When Direkt36 asked NAV for guidance on this, they replied that we should direct our questions to the Prime Minister’s Office. They did not elaborate on what the government apparatus had to do with the issue of private equity funds, which in principle belongs entirely to the business world. The Cabinet Office, however, responded to our inquiry by saying that “we strongly refute even the suggestion that the Prime Minister’s Office has any jurisdiction over the ownership registry of Hungarian private equity funds”.

We asked for reactions to our article from all relevant fund managers and beneficial owners but received no response from most of them. Two fund managers – Quartz and Opus Global – replied that they could not disclose information about owners and investments. Among other things, Áron Hornung wrote that we were inaccurate about him, but he declined to specify which of our claims he disputed. Közép-Európai Kockázati és Magán Tőkealapkezelő Zrt., which according to the NAV database manages Hornung’s funds, said that the database contained incorrect data due to a bank administrative error, but did not specify who the real owners of the funds were. (Update: After the publication of our article, 4iG’s head of communications indicated that two private equity funds were wrongly linked to Lőrinc Mészáros in the database – presumably also due to a bank administrative error – and that they are in fact owned by Gellért Jászai, the head of 4iG.)

Main findings

According to Direkt36’s research, out of the total of 119 private equity funds registered by the Hungarian National Bank, 37 reported their beneficial owners to NAV’s system, but 11 of these only identified persons who, as managers of the fund, can make decisions about the investment of the fund’s money, but do not have a stake. The extent of their interest varies between 39 and 100 per cent.

Of those with an interest, 17 private equity funds belong to clearly pro-government owners, but a further five are also closely linked to pro-government business circles. Among them are well-known billionaires such as István Száraz, László Szíjj, Lőrinc Mészáros, Zsolt Hernádi and Gellért Jászai. Lőrinc Mészáros is the most prominent: he has a 100 per cent stake in nine private equity funds, and another two belong to his corporate lawyer, József Tamás Kertész.

These are what we found out about the funds:

- Lőrinc Mészáros’ private equity funds are in fact even more extensive than the collections published in the press so far have shown. The Manhattan and Repro I private equity funds have so far been linked to Gellért Jászai because he owns the fund management company, but the actual ownership records show that the 100 per cent ultimate beneficial owner is Lőrinc Mészáros. At present, one property in Normafa is linked to Repro I, and Manhattan owns 1.6 percent of the shares in the IT giant 4iG, which is managed by Gellért Jászai. (Update: After the publication of our article, the communications manager of 4iG amended that the two private equity funds have actually been owned by Jászai Gellért for years, and the NAV records contain outdated data. The banks managing the accounts are responsible for updating the data and identifying the actual owners.)

- Private equity funds called Eirene and Metis, which own almost 15 percent of the shares of Magyar Bankholding, the Hungarian superbank to be established this year, were previously known to be linked to Lőrinc Mészáros through the fund manager Opus Global, now the actual ownership records officially indicate too, that the shares actually belong to Viktor Orbán’s friend.

- It has also become certain that the giant private equity fund Konzum PE’s ultimate beneficial owner is Lőrinc Mészáros. The Hungarian press, for example Átlátszó and Válasz Online, has been following in detail the investments of the fund, which is the largest owner of Opus Global Plc, the flagship of the Mészáros business empire. In addition, it owns several large food companies and a mineral water company, the Hunguest Hotels hotel chain and the Balatontourist camping network, as well as several lavish Andrássy Avenue properties in Budapest.

- According to the beneficial ownership registry, Mészáros also owns the private equity funds Global Alfa, Status Next, Status Food and Status Property. These include, among others, interests in the turkey processing company Gallicoop, a PET recycling plant in Karcag, the former officers’ casino palace near Ferenciek Square in Budapest, which used to be the headquarters of MKB Bank, and the transformer manufacturer Ganz Ltd. The latter was partially acquired by the private equity fund Prime Property early last year. Along with Prime Finance, this private equity fund is not owned 100 percent by Lőrinc Mészáros, but by one of his confidants, the lawyer József Tamás Kertész, who often handles the legal affairs of his companies. Kertész also works for 4iG and is the founder of the government-owned media foundation KESMA.

- István Száraz, who is a friend of Ádám Matolcsy, the son of the Hungarian National Bank’s president, ultimately owns 10.8 per cent of the shares in the new superbank, Magyar Bankholding, which will be created later this year. This was not clear until now, only that the ultimate beneficial owner of the shares is Uncia private equity fund (indirectly through two Luxembourg companies, both called Blue Robin, and two other Hungarian companies). Now, the beneficial ownership records show that this fund is 100 per cent owned by István Száraz.

- István Száraz appears to be the beneficial owner of another private equity fund, too. According to the register, he has a 100 per cent in Felis private equity fund. The fund is managed by Quartz Fund Management. Quartz, formerly owned by Mr. Száraz and now owned by a private equity fund, manages a range of investment funds and thus holds billions of HUF in assets. Válasz Online has previously found Felis behind a number of companies, including the premium deli chain Culinaris, the Black Swan cocktail bar in the Pest party district and the Pine Weekendhouse in Balatonkenese. The latter was backed by state tourism funds. Felis Private Equity Fund used to be the owner of the Lánchíd 19 Design Hotel near Várkert Bazár. The same is the case with one of the most exclusive plots in the Buda Castle District at Ostrom Street. It also owns a large office in Vörösmarty Square.

- A name not previously reported in the press emerges as the 92 and 93 percent owner of the private equity funds Közép-Európai I and Közép-Európai II, which formerly owned the Dürer Garden property. These funds can also be linked to István Tiborcz’s business partner and friend Bálint Szécsényi, as he runs the company managing them. However, the actual owner listed in the ownership register is not Bálint Szécsényi, but a certain Áron Hornung, who is linked to István Tiborcz’s business circle. Hornung is from the Southern Hungarian town Pécs and works there as a real estate agent and office manager of the Duna House real estate agency. In the meantime, however, he also owns or has owned billions of HUF in assets through his companies. For example, he founded a company called PLZ-Asset, which bought Pécs Plaza, then in 2020 was bought by a real estate fund of one of the country’s richest men, real estate investor Daniel Jellinek. The same happened to PLZ Office, a company that owns an office building in Pécs. It was also set up by Hornung and has since been acquired by Jellinek. Fagales Zrt., a real estate management company founded in 2017, of which Hornung is both the CEO and sole shareholder, has brought Hornung huge profits, and last year had a net profit of nearly HUF 10 billion. Hornung has approved a dividend payment of 13.5 billion forints to himself, according to public company documents. Hornung’s extraordinary business success went unnoticed in the press despite the fact that Fagales Zrt. was among the top 500 companies for 2022 as the most profitable company in Baranya County. Hornung also knows Endre Hamar, a former schoolmate and business partner of István Tiborcz in Pécs. Hamar and Hornung are not only Facebook friends, but in photos uploaded to Facebook in 2010 they are sitting at the same table in a club. (Közép-Európai Kockázati és Magán Tőkealapkezelő Zrt., which manages the funds, sent a statement shortly before the publication of this article stating that Hornung is not the real owner of the private equity fund, but that there was only an administrative error at the bank, but still did not say who the real owner was, citing legal reasons. When contacted, Áron Hornung replied that he and his family had been involved in real estate investment for nearly 20 years and called our claims untrue and inaccurate on several points. However, he declined to specify exactly which allegations he disputed. István Tiborcz’s communications manager promised to answer our questions later, and Endre Hamar’s law firm declined to respond. Dániel Jellinek told Direkt36 that to his knowledge, Áron Hornung is a well-known real estate owner in Baranya County, who managed to turn Pécs Plaza into a well-managed project, which is why Jellinek’s Indotek Group decided to buy the shopping centre from him.)

- Zoltán Szabadics, an entrepreneur from Zala County, is the 100 per cent beneficial owner of the Közép-Európai VI private equity fund, according to the NAV registry. Szabadics’s father, József Szabadics, founded the family’s construction group, and Zoltán holds senior positions in several of the group’s companies. He is also the chairman of the board of directors of BAHART, a Balaton shipping company belonging to the state’s Tourism Agency, and has also received a medal from former President János Áder. One of his companies received a HUF 1.7 billion grant from the state Kisfaludy programme. The Közép-Európai Kockázati és Magán Tőkealapkezelő Zrt., which manages the fund, stated shortly before the publication of our article that Szabadics was not the real owner of the private equity fund, and that there had been an administrative error in the bank mixing up the data, but still did not say who the real owner was, citing legal reasons.

- Zsolt Hernádi, CEO of Hungarian oil company Mol, is not only the manager of the Solva private equity fund through a company, but is also a 100 per cent owner, the beneficial ownership register shows. The fund has previously bought a company and two hotels in the town of Esztergom.

- László Szíjj, Lőrinc Mészáros’s billionaire business partner, also appears in the beneficial ownership database as the owner of a private equity fund called Themis. This means the fund is not only managed by his company, but the billionaire is also the beneficial owner. This fund (in consortium with seven other private equity funds) won the procurement process offering the right to operate Hungarian motorways for 35 years.

Below you can see the ultimate beneficial owners, who are businessmen close to the government or persons connected to them:

| Name of private equity fund | Beneficial owner(s) | Percentage of interest |

| EIRENE | Mészáros Lőrinc | 78 |

| EKHO | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| Felis | Száraz István Péter | 100 |

| Global Alfa | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| iG TECH | Jászai Gellért Zoltán | 100 |

| Konzum PE | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| Közép-Európai I. | Hornung Áron | 93 |

| Közép-Európai II. | Hornung Áron | 92 |

| KÖZÉP-EURÓPAI VI. | Szabadics Zoltán | 100 |

| Manhattan | Mészáros Lőrinc* | 100 |

| METIS | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| PRIME FINANCE | Dr. Kertész József Tamás | 100 |

| PRIME PROPERTY | Dr. Kertész József Tamás | 100 |

| REPRO I. | Mészáros Lőrinc* | 100 |

| Solva | Hernádi Zsolt Tamás | 80 |

| STATUS FOOD | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| STATUS NEXT | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| STATUS PROPERTY | Mészáros Lőrinc | 100 |

| THEMIS | Szíjj László | 100 |

| UNCIA | Száraz István Péter | 100 |

(For the other identified beneficial owners, no clear public or political affiliation was found, so we decided not to disclose their names.)

(After publication, Gellért Jászai’s 4iG has said, these private equity funds currently belong to Gellért Jászai.)

How come private equity funds appear in the beneficial ownership registry?

It is probably because the system was set up barely a year and a half ago, and because of the complexity of the regulations, that made it possible that some of the beneficial owners of private equity funds have appeared in the NAV registry.

The 2021 law on the establishment of a de facto register of beneficial owners does not name private equity funds, so they are not specifically covered by the regulation, which means they can continue to keep secret who their main investors are. However, they do have bank accounts and another law, the Anti-Money Laundering Act, requires banks that maintain accounts to keep records of the beneficial owners of legal entities. Thus, the beneficial owner of some of the private equity funds may appear in the NAV register even though they should not be there officially.

As the law and the database are new and the regulation is complicated, banks appear to have chosen different solutions of declaring who owns the funds and who should be considered the beneficial owner. A guide on how to determine the beneficial owner in complex cases – “complex ownership structures” – is available on the Hungarian National Bank’s website. And while it is detailed and covers a lot of subjects from identifying foremen to dealing with offshore companies, it does not specifically address the case of private equity funds.

But in their case, it is not at all clear who the beneficial owner should be: the person holding the majority of the shares (at least 25 per cent according to the law)? Or the manager of the management company? In the case of private equity funds, the people who put their money into the fund cannot formally decide how it is invested, because this is decided by the management of the company managing the private equity fund. However, these managers do not have a share in the fund, so profit always goes to the investors.

In the Hungarian practice however, personal links between the fund manager and the owners of the fund are presumably very common. This is also shown by documents downloaded by Direkt36, which basically show that people with shares in private equity funds also have influence on the fund management companies, or even own them outright.

The EU created it, the Curia ruled against it

As part of the fight against money laundering, the European Union already instructed Member States in 2015 to start keeping a central register of beneficial owners of companies and other legal entities registered in their territory. Such a database is a dream of investigative journalists and anti-corruption organizations, as it makes it harder for owners hiding behind offshore companies to hide their assets. However, investors seeking to increase their wealth in secret were clearly not happy about this.

Member States were reluctant, with only a few of them having created the database by the 2017 deadline. In the meantime, partly in response to the scandal induced by the publication of the Panama Papers stories, which exposed a series of offshore secrets, the EU has moved even further towards transparency, and a subsequent 2018 directive required that the identity of beneficial owners be made public. This means that not only public authorities but also ordinary citizens have the right to know the identity of the beneficial owners.

The actual ownership registers were then established in this spirit across Europe. Hungary was one of the last in 2021. The register is managed by the tax authority, and banks are required to report the data to the system monthly. The banks are entrusted with this task because they manage the accounts of companies, subsidiaries, law firms, pension funds and a range of other legal entities. At the opening of the account and later, in the event of a change of details, banks are obliged to ask their customers for a declaration of the identity of the beneficial owner, which they forward to the NAV register. In principle, mainly authorities have access to the database, but under EU rules, anyone can know the identity of the beneficial owner by paying HUF 1 500 (approx. 4 euros) per account.

However, the Hungarian system, which came into operation in 2021, may not be with us for much longer. The EU has seen a series of lawsuits against the disclosure of data, and at the end of November last year, the Court of Justice of the European Union, the Curia, ruled that it is not okay for anyone to know the identity of the actual owners.

Only a few hours after the ruling, Luxembourg switched off its own registry, and the Netherlands followed suit the next day. In the following days, Austria, Belgium, Malta and Germany also ended open access. The Hungarian system is still available.

Dániel Szőke contributed to this article.