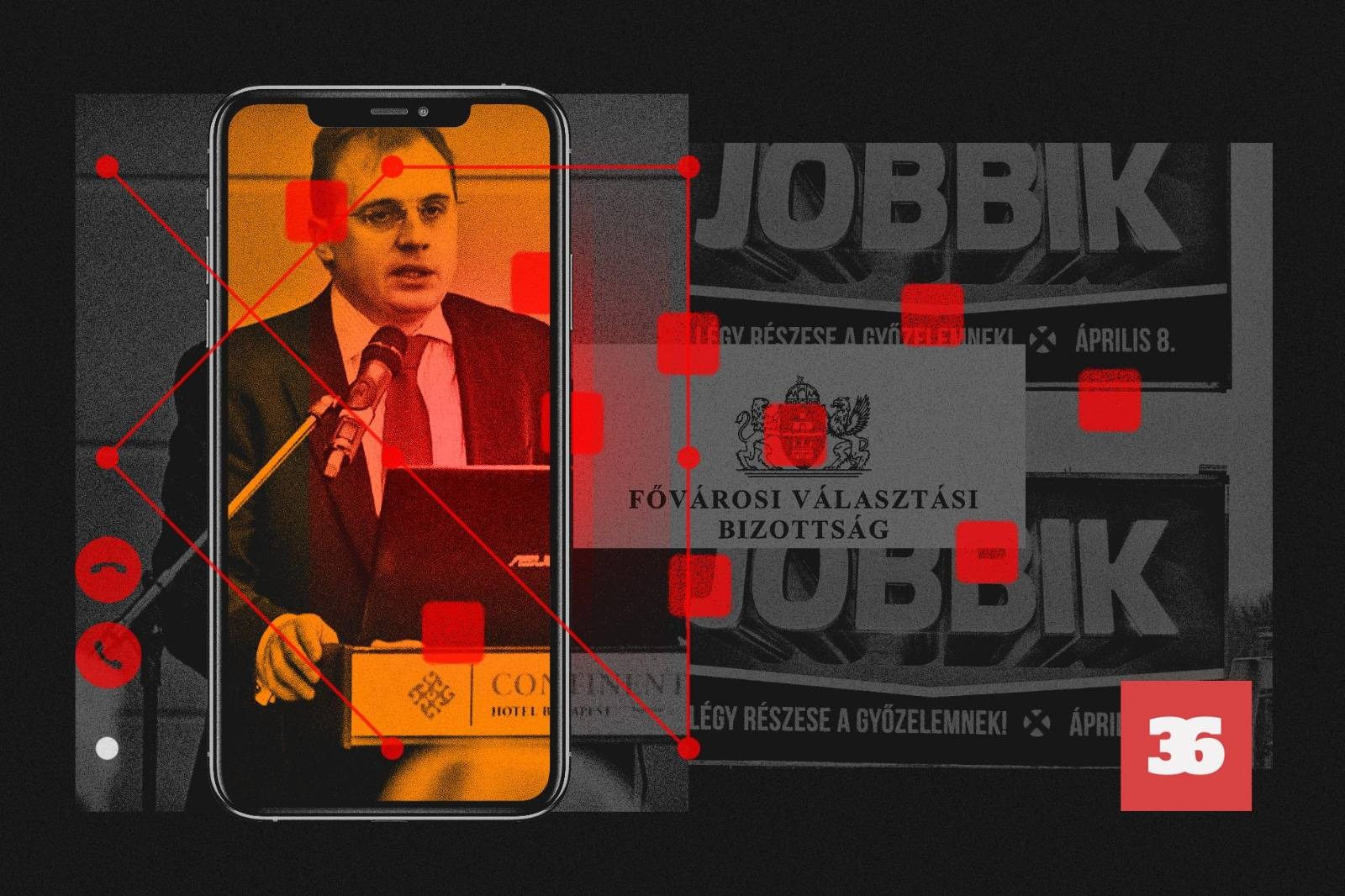

Another Pegasus target with political ties: a lawyer who oversees elections and worked for opposition party Jobbik

László Vértesy’s name is probably not known even to people who closely follow the news, although the lawyer who teaches at the University of Public Service has long been involved in politics. For years, he was a researcher at the pro-government Századvég Foundation and then did similar work for the opposition party Jobbik before the 2018 parliamentary election. What’s more, since 2014 he has been a member of the Metropolitan Electoral Commission, which oversees the legality of the elections.

According to Direkt36 investigation, Vértesy has also been one of the Hungarian targets of Pegasus spyware. Two phone numbers used by Vértesy are part of the leaked database of more than 50,000 numbers containing targets selected for targeting by foreign clients of NSO Group, the Israeli company manufacturing Pegasus. The database was obtained by Forbidden Stories, a Paris-based network of journalists and international human rights organization Amnesty International, and it became the basis of a global investigation of 17 media outlets, including Direkt36 from Hungary.

Vértesy declined to answer our questions, and it wasn’t possible to analyze any of his phones to find out whether they were hacked. However, for other Pegasus targets on the leaked list, forensic analyses have shown in a number of cases that spyware has indeed infected the targets’ devices.

The database containing the telephone numbers of Pegasus targets does not reveal who used the spyware – sold exclusively to governments and state agencies – against Hungarian targets. However, senior Fidesz politician Lajos Kósa recently publicly acknowledged that the Orbán government had acquired and used the Israeli tool. We have previously identified journalists, media company owners critical of the government, opposition politicians, as well as government and national security officials among the targets.

It is not clear why Vértesy became a target. His acquaintances interviewed by Direkt36 are not aware of any official investigations against him that could have justified his targeting. Pegasus was directed at him in the early fall of 2018 and based on information from his acquaintances and publicly available data, nothing happened to him at that time that could easily explain why he became a target.

It is known, however, that he still had politically sensitive roles during that period. Vértesy was a member of a Metropolitan Electoral Commission. One the commission’s responsibility is to investigate reports of suspected violations of electoral rules.

Vértesy was first elected to this position in 2014, when the municipality was run by the governing Fidesz party. In August 2019, shortly before the municipal election that was won by the opposition, he was re-elected by the metropolitan assembly. A current municipal source told Direkt36 that Vértesy had not joined the board as a party delegate, but at the suggestion of the chief notary working in the Fidesz-led municipality.

At the time of becoming a target, Vértesy was the owner and manager of a company called the Civitas Institute, which helped Jobbik before the parliamentary elections in April 2018. However, according to sources familiar with the party’s affairs, Civitas was no longer active during the Pegasus targeting period, and Vértesy did not have a closer relationship with the party.

However, the timing of the targeting is not necessarily relevant. If Vértesy was indeed under surveillance, it is also possible that the users of the spyware wanted information about an earlier period. Pegasus gives access to all information that is already on the phone: emails, messages, photos, videos, and voice recordings from months or years before.

One of Vértesy’s aquintances told Direkt36 that he also did not understand why he might have become a Pegasus target.

Vértesy teaches at the University of Public Service (NKE), which also serves as a recruiting base for the government and state agencies, but his research field is not sensitive from the point of view of national security. He teaches financial and economic law at the Department of Administrative Law. Although current laws allow any employee of NKE to be subjected to so-called “due diligence” inquiries, in which surveillance techniques can also be used, this rule was only introduced in 2021. So, it was not yet in force when Vértesy became a target.

The government did not respond to Direkt36’s questions about Vértesy’s targeting.

A member of the “inner circle”

According to his university CV, Vértesy, who studied economics in addition to law, started to work for the pro-government Századvég Foundation in 2013, but then a few years later he switched to Jobbik, one of the strongest opposition parties back then. According to sources familiar with the internal affairs of the party, this was a period when the previously radical rightwing Jobbik was trying to reposition itself as a more moderate political force and attracted a new group of academics and experts, including Vértesy.

“At the time, it seemed that Jobbik could be the strongest challenger to the government, and that attracted intellectuals to them,” one source explained.

In the fall of 2017, Vértesy founded a company called the Civitas Institute, which organized conferences and other events with the participation of opposition politicians, as well as producing background materials on topics important to the Jobbik. Civitas commissioned the publication of the Black Book of Corruption, a list of the major corruption cases under the Orbán government. The report was prepared by the Hungarian branch of Transparency International.

Vértesy was also in close contact with Jobbik’s leadership. “During the making of our program, he took part in the discussions as the leader of the Civitas and thus worked as a member of the campaign team,” said János Volner, the party’s former vice president, who has since left Jobbik and became one of its harshest critics.

Other sources from Jobbik also confirmed that Vértesy was involved in the campaign work, and some noted that he would have been expected to work for the government in case of an election victory. Vértesy also appeared a few times at a series of events organized by the newspaper Magyar Nemzet, owned by oligarch Lajos Simicska at the time, where, politicians from Jobbik and other opposition parties discussed strategies about how to defeat Fidesz.

The defeat in the 2018 election eventually plunged Jobbik into a serious crisis. President Gábor Vona resigned first, and in the following months several other former leading politicians of the party also left. The infighting continued even in the fall, when Vértesy became a Pegasus target. According to sources in Jobbik, however, Vértesy was no longer active within the party. “As far as I can recall, Vértesy was not visible near the party after the election,” Volner said.

According to those familiar with the party’s affairs, the Civitas Institute, which was owned and run by Vértesy until October 2020, was no longer active during this period either. (The institute was revived for the upcoming elections in April 2022. It is organizing events and has been working with Transparency International on a new updated edition of the Black Book on Corruption.)

One of Vértesy’s acquaintances told Direkt36 that the lawyer probably regretted helping Jobbik. A source requesting anonymity said he had met the lawyer several times before the 2018 election, and Vértesy “suggested that this was an opposition activity” that could have a damaging effect on his later career. Vértesy’s official CV on the NKE’s website does not even say that he ever had anything to do with the Civitas Institute.

After the lawyer’s departure, the new owner of Civitas Institute became Levente Nagy-Pál, one of the assistants of Jobbik politician Márton Gyöngyösi, a Member of the European Parliament. One of the directors of the institute is Zoltán Kész, a former member of parliament and one of the close political allies of the opposition’s prime minister-candidate Péter Márki-Zay.

Opposition targets

Direkt36 has previously revealed that there were several opposition-linked individuals targeted by Pegasus spyware.

Before the 2018 elections, the targets also included the son of oligarch Lajos Simicska, who supported Jobbik at the time, and one of the oligarch’s closest confidants. At the end of 2018, György Gémesi, the opposition mayor of Gödöllő, appeared among the targets. Last year, Zoltán Páva, the publisher of an opposition website was surveilled with Pegasus. His surveillance started when it became public that he was advising the opposition party Democratic Coalition led by former prime minister Ferenc Gyurcsány.

The government has not commented on any of the cases and did not acknowledge that they had anything to do with these people becoming targets. However, Gergely Gulyás, the head of the Prime Minister’s Office, once stated that some of the press reports on Pegasus surveillance had factual basis. However, he did not specify which cases he was referring to.

Cover picture: szarvas / Telex